With a name like ‘Yik Yak’ (and an actual yak as the app icon), you’d be hard pressed to figure out exactly why the app is making waves across US college campuses.

Simply put, Yik Yak is to the college community what Secret was to the tech community: a way to share things anonymously with people in your ‘network’. The difference with Yik Yak is that the network is physical, limited to a 1.5 mile radius from your location.

Having gained huge popularity since it’s debut last year, Yik Yak has seen the beginnings of apps like Facebook and Snapchat. It’s currently one of the top 10 social networking apps in the App Store and has just gotten another $75 million in funding. But despite its success, it’s also seen a lot of controversy.

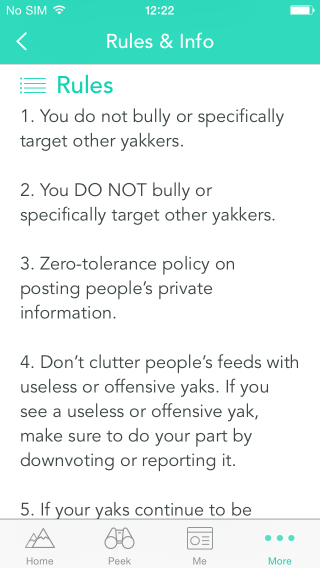

With anonymity comes the typical sense of freedom to post derogatory, nonconstructive and damaging things, just because you can get away with it. As a result, Yik Yak has experienced no shortage of media coverage blasting the app for encouraging bullying among high school and college students.

Once again, it looks like a social app is redefining the high school and college experience (think about college life before Facebook), but is it doing more harm than good this time around? Let’s take a closer look at Yik Yak to find out and to see if, like Facebook, it can survive off campus.

What is Yik Yak?

Like a combination of Secret and Whisper with a bit of Twitter thrown into the mix, Yik Yak is an anonymous social network that lets you post updates to a Twitter-like news feed to people within a 1.5 mile radius to read. Twenty-three year old developers Tyler Droll and Brooks Buffington call it a “virtual bulletin board” for college campuses, but are hoping that it’ll eventually turn into a hyper-local news source.

How does Yik Yak work?

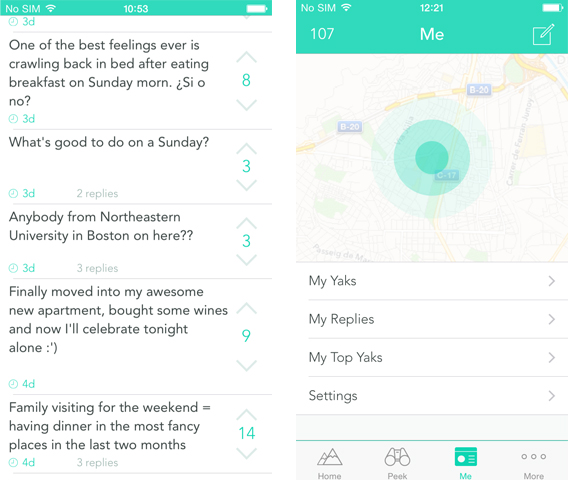

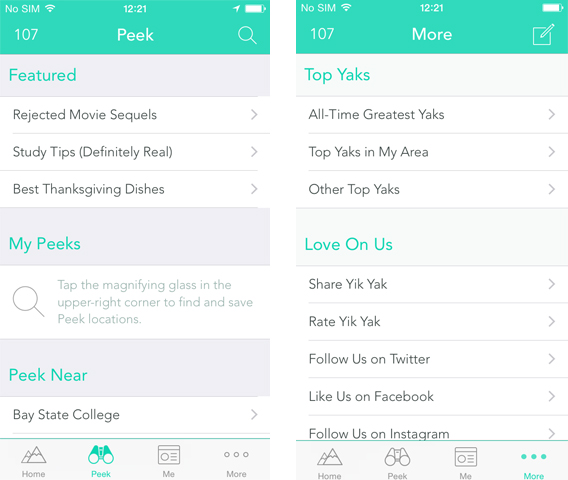

The app is simple. No login or registration is necessary. Simply download the app, and you’ll have access to a feed of posts– known as Yaks– within a 1.5 miles of you. Similar to Reddit, posts can be up or down voted; up votes mean posts get more visibility, while enough down votes can get a post removed from the app. You can also anonymously comment on posts. Similar to Twitter, posts are limited to 200 characters. although unlike Twitter, they expire after 100 days.

While you can only see ‘Yaks’ from people in your 1.5 mile vicinity, there’s a section for Featured posts with trending topics, a Top Yaks section for the most popular posts, and a section called Peek Near, a voyeuristic look– without the ability to comment or post– at what’s going on at colleges across the US.

Why is it so popular?

Like Facebook and Snapchat before it, Yik Yak has found a rampant following among high school and college students, the implicit seal of approval for a social app. Kids see it as a way to anonymously share things going on around campus, and because it’s linked to where you are at the time, you end up contributing to a very local network. More than revealing some big secret to a bunch of strangers, Yik Yak is a kind of sounding board to vent frustration about things which people around you might actually understand.

With little promotion, the developers have said that they targeted heavy users on campuses to help spread and promote the word about the app. It worked.

Why all the controversy?

While anonymity is the draw of the app, it’s also what’s been causing the biggest controversy. Plain and simple, kids can be mean. What’s supposed to be a ‘virtual bulletin board’ has turned into a public hub for bullying, bigotry, and bomb threats. High schoolers have been particularly guilty of using the app for evil instead of good.

Imagine this: A student anonymously posts a derogatory comment about another student, identifying them by name, and immediately, whether its true or not, the entire school knows the rumor. Yet no one takes the blame, because the comment was posted ‘anonymously’. Not surprisingly, this has already happened in countless schools across the country.

Far more damagaing are the ‘anonymous’ threats sent via Yik Yak, which have forced school lock downs pending investigation into their legitimacy. While there’s so far been no merit to most of these threats, there have been real repercussions for those students involved.

What are the developers doing to control it?

Threats and bullying are clearly not the intention that developers Droll and Buffington– themselves recent university graduates– had for the app, and they’ve been working both proactively and reactively to alleviate some of the tension that it’s caused in schools.

Threats and bullying are clearly not the intention that developers Droll and Buffington– themselves recent university graduates– had for the app, and they’ve been working both proactively and reactively to alleviate some of the tension that it’s caused in schools.

In terms of threats, Droll and Buffington have cooperated with authorities, like in the case of a threat made at the University of Albany, SUNY, to identify the students involved.

It’s mostly kids venting about classes or finals, making dumb jokes, or posting drunk confessions.

Proactively, they’ve been working to keep Yik Yak out of high schools altogether. They’ve implemented geo-fencing to prevent the app from being accessed in high schools, meaning that if you’re on or around high school grounds, you can’t post anything or see feeds. A lot of it has been done voluntarily by Droll and Buffington after hearing reports of bullying and threats across the country, and with the help of Maponics, who had already mapped out 85% of highschools in the US, they were able to quickly implement geo-fencing in many schools across the country.

There’s also a bit of what Droll and Buffington call ‘self-policing’, in which posts that are negative or offensive get downvoted, and subsequently removed from the feed, although it’s still unclear as to how many down votes something needs before it gets removed. There’s also the option of flagging inappropriate yaks.

What’s the future of Yik Yak

Like Facebook before it, Yik Yak is taking a page from the social media book of success, targeting college students first in the hopes of building upon this success to expand beyond college campuses. Droll and Buffington have been vocal about the fact that they see Yik Yak as more of a “hyper local news source” than just a sounding board for angsty high schoolers and drunk college kids. For now though, those drunk college kids are still their target market, which is painfully obvious from the promotional video below.

It’s hard to say whether or not Yik Yak could have a future outside the college bubble, especially when you look at the kind of stuff being posted: it’s mostly kids venting about classes or finals, making dumb jokes, or posting drunk confessions. Obviously, it’s not all dangerous, but it’s also not all that useful. The question is, do you care as much about strangers complaining on the subway as you do about people sitting next to you on campus? The local community feel about Yik Yak seems like it’s most valuable feature (along with anonymity), and it could be hard to recreate in the ‘real world’.

Who knows if anyone will actually care.

As far as a hyper-local news source, it’s 1.5 mile radius could be more of a detriment once the app ventures off campus. You’ll only get ‘news’ if you’re in a very specific area, and to be honest, Twitter and messaging apps like WhatsApp have already got the breaking local news thing pretty much covered.

Yik Yak’s biggest point of contention is its anonymity, both a selling point and a potential threat. Right now, the app is still causing a lot of controversy because of the apparent attraction of sharing non-kosher thoughts anonymously to people who might actually know what you’re talking about. Beyond that, as we’ve seen with the seemingly forgotten Secret and Whisper, once it goes out into the real world, it could get boring, fast. Who knows if anyone will actually care.

Then again, Facebook started in the same way, and look where it is now. There are many who hope the app’s buzz is just a fad. Only time will tell.

Related articles:

Why Rooms is not the future of anonymous chat

‘Anonymous’ social networks like Secret fail to provide anonymity

Fitness apps and location tracking: risk or reward?

Follow me on Twitter: @suzieblaszQwicz