Crowdsourcing has become popular with everything from gathering general information (Wikipedia), to photo sharing (iStockphoto) to rallying support for artist tours (Songkick Detour).

Most recently, crowdsourcing has gone mobile with apps for your smartphone that harness the power of the crowd to share information, improve a service, or even teach you something new. Here, I take a look at what crowdsourcing is all about, what it can do and how well it works on the mobile platform.

What is crowdsourcing?

Crowdsouring means having a large group of people contribute to a service or need, generally in an online community, and usually to improve that service. Even if founder Jimmy Wales dislikes the term, Wikipedia is one of the best known uses of crowdsourcing, which lets anyone on the web contribute information to pages about any and every topic under the sun. Its appeal is a pool of over 77,000 knowledgeable expert volunteer editors that provide information and quality control for a ton of different topics, giving it a huge database and making it one of the first go-to websites for finding information about any topic online.

When it comes to mobile apps, social networking site Twitter can be seen as a good example of one of the first uses of mobile crowdsourcing, especially its use to break, corroborate, or dispel news stories or events from people on the ground at the point of action, like during the London riots in August 2011.

In these two examples, trust seems to be the number one consideration for gathering information, and this trust is based on numbers: the more people writing about it, using it, or witnessing it, the more reliable the information tends to be.

So, how has this concept of crowdsourcing as it relates to trust in numbers been translated to mobile apps? I’ll take a look at a couple of the most interesting ways that crowdsourcing has been used by mobile app developers to improve upon, or even create, a service or need.

Gathering and reporting real-time data

Traffic

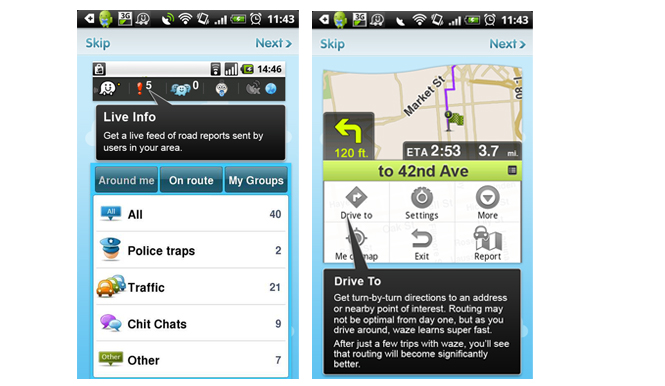

Waze is one of the most well known and best uses of mobile crowdsourcing on the market; it takes live traffic information from users on the road to give real-time reports on road conditions. The beauty of crowdsourcing for reporting traffic? It’s instantaneous! Traffic reports on the radio can sometimes lag, and when you’re trying to get somewhere quickly, Waze is the perfect solution. It also gives alternative routes in case the delay is longer than anticipated, as well as warnings for police traps.

Its availability on many different mobile platforms (iPhone, Android, Blackberry and Symbian) opens up the potential for even more users to add to its already large pool of 50 million (something Google was more than aware of when it bought the Israeli company this past June). Similar transport apps like HopStop (also recently acquired by Apple) make good use of crowd sourced information for reporting travel conditions too.

Weather

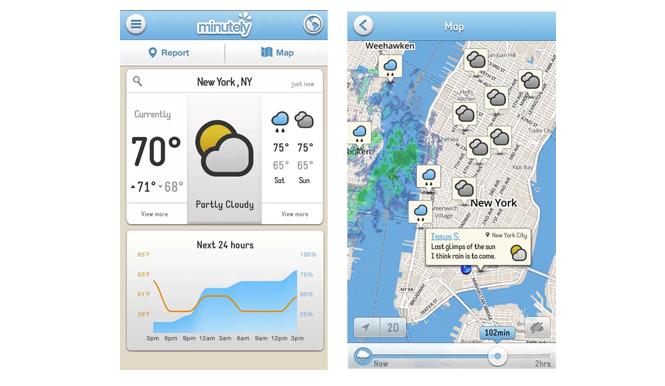

I can’t count how many times I’ve looked at my cell phone’s built-in weather app only to step out the door and experience something completely different. Mobile apps like Weathermob, Weendy and Minutely help solve this problem by using real-time weather reports from people in specific locations. This can be really useful in big cities, where the weather changes from one side of town to another, or if you want to know the weather conditions in the next city over.

These aggregated user reports make the reported weather conditions within the apps more reliable because they come from many different sources, not just one single weather station.

They’re also constantly adding new and interesting features, like Minutely, which has recently added 3D radar to its weather reports. A lot of social media aspects have been added to these apps as well, and since weather is always a good (or bad) conversation topic, it seems like a good fit.

That being said, a good weather forecast is also about being able to predict what the weather will be like in the [near] future. For this reason, weather seems like less of a home-run when it comes to crowdsourcing, at least in terms of predictability.

Cell coverage and Wifi hotspots

Want to know how well your cell phone network is covered in a certain area? Most people do, and Open Signal is an app that can help do that. If you’re having trouble with your cell phone signal, you can access the Open Signal map to see the strongest signal in you location, a compass with the direction of your cell phone provider’s closest tower, and even where you can get Wifi. The best part? Just by using the app, you’re contributing to the accuracy of signal strength data: the more people that use the app, the more accurate the information it provides will be.

Music

Request a song

Music is always one of the first things to experiment with when it comes to mobile apps, and crowdsourcing is no exception.

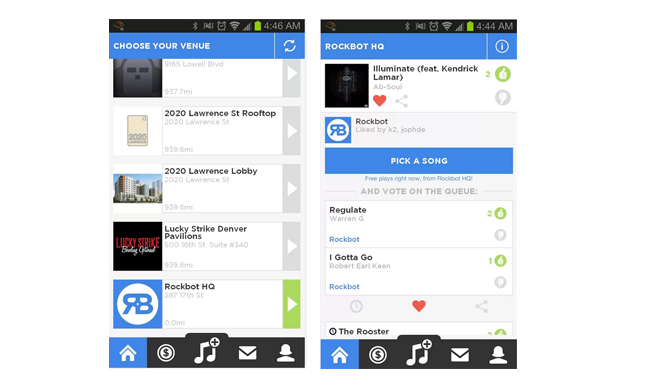

Rockbot, for example, lets users add songs to the music queue at participating venues. Think of it as a remote-controlled jukebox. It’s a pretty simple concept: you find a participating venue (restaurant, bar, etc.), choose from a list of thousands of songs from varying genres, and add it to the queue. That’s it. In no time, you’ll be able to hear your song playing in the venue.

It’s already available in hundreds of locations across the US, and although it’s a pretty interesting concept, it’s use is still fairly limited.

Education

Learning

Duolingo is an app that lets you learn a language by completing short exercises, both written and verbal. So where does crowdsourcing come into play? After completing a few exercises, you get the chance to translate real webpages online. The more people that complete the translation, the more accurate it will be. You get a percentage score to see how similar your translation is compared to other people’s translation of the same text. A pretty clever idea, but it could be problematic for beginner levels of the app, where people are more likely guessing at than making accurate translations.

Research

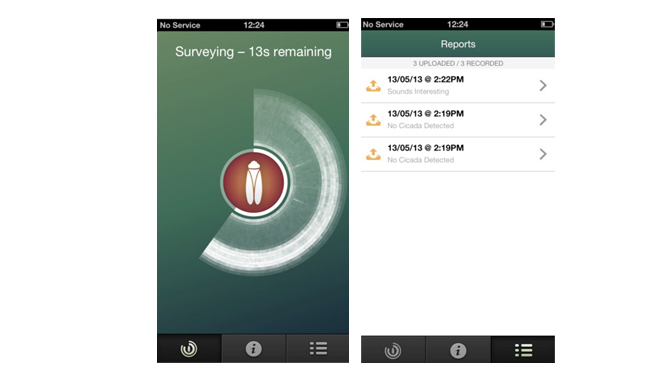

One of the more unique and interesting uses of crowdsourcing is Cicada Hunt, an app that lets you record your surroundings in the hopes of finding the rare New Forest Cicada, an insect with a specific high-pitched song whose last unconfirmed sighting was in its native UK in 2000. Once you’ve recorded the sound with your phone’s speaker, you can get immediate feedback about what you’ve heard.

By completing the quick audio survey, the information you’ve recorded and your location are transmitted to researchers who can analyze it further. So Cicada Hunt not only lets you learn a little bit about nature, it also gives you the chance to contribute to research on the New Forest cicada.

Mobile crowdsourcing: A great success?

It seems like the best use of crowdsourcing for mobile, unlike its use on the web, is for real-time data and live information. Reporting live and being able to use this information immediately fits well with the instantaneity that cell phones (and their users) demand. What these apps really come down to though, is the number of people using them. The more people that use it, the more reliable and useful the information they are providing will be.